Countries

Countries as Systems

Countries in Context

I believe that countries are usefully seen as human social systems. The workshops on this topic will either show that or not, depending on whether my systems thinking tools prove to be useful in understanding them. Until then, I will assume that they are, based on a simple definition that may require further refinement later.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines a system as

a set of things working together as parts of a mechanism or an interconnecting network; a complex whole.

It has a second definition of

A set of principles or procedures according to which something is done.

These are related and for the time being, I will define a human social system as a set of people working together according to a set of principles or procedures. This is somewhat vague for now; I expect to have to refine it later. I currently think of it as including such things as countries, schools, healthcare systems and economies but I expect to learn more about how well the tools for thinking about human social systems apply to all of these. Some of these systems may also have subsystems. For example, a school may have an administration as a subsystem and a democracy may have a legislature as a subsystem.

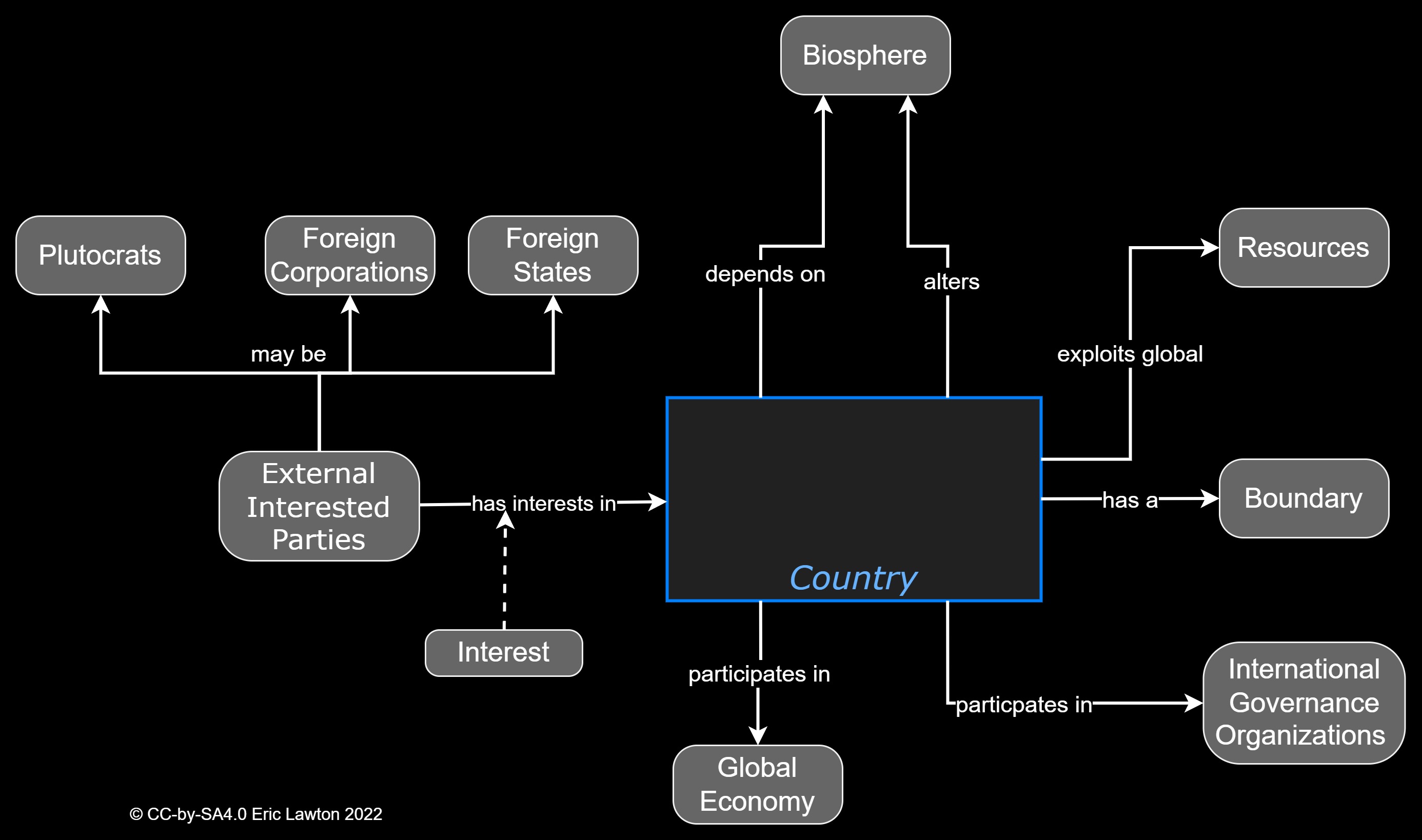

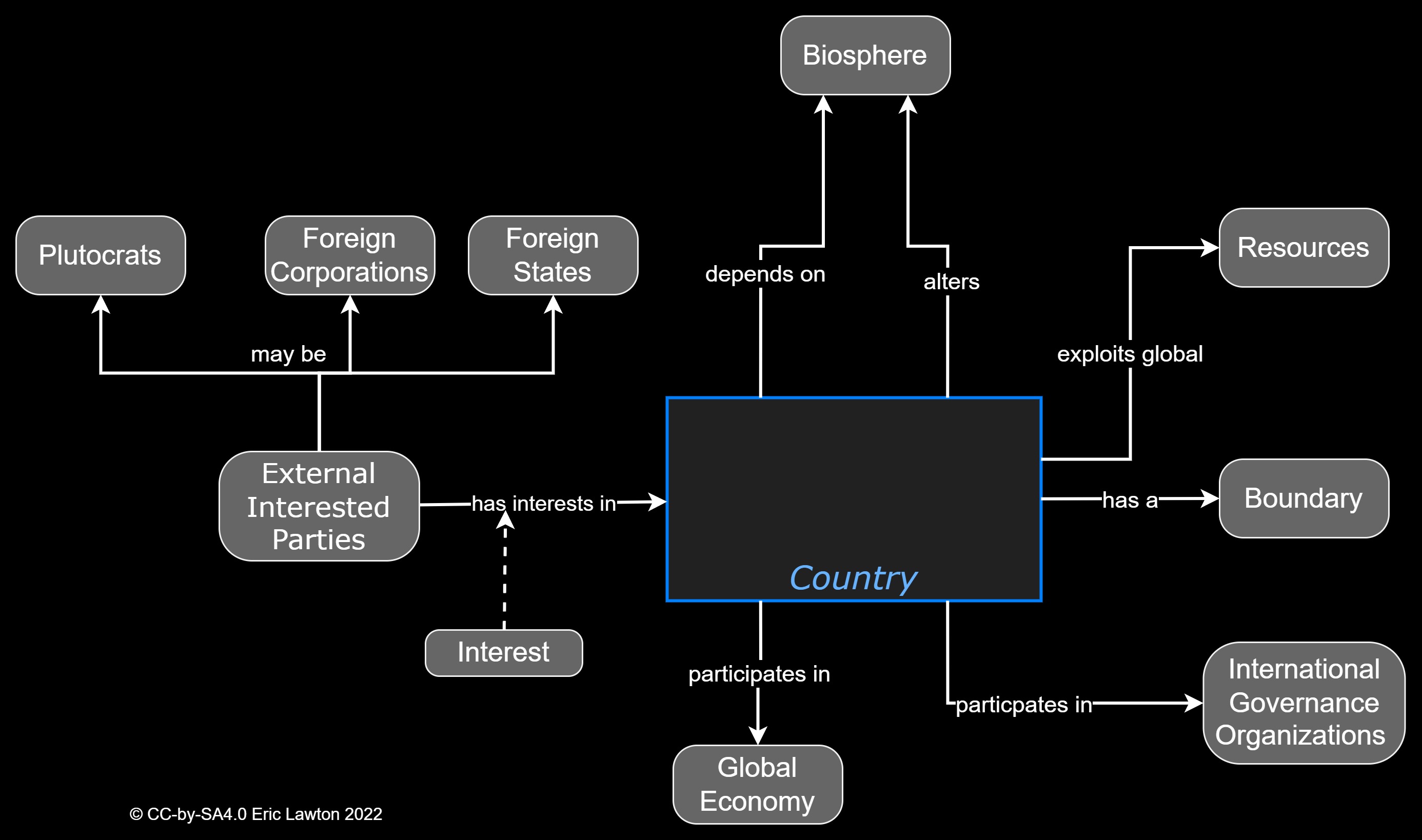

In order to start to understand a system, it helps to know how the system interacts with its environment, which I usually start with drawing a System Environment Diagram. I already had a similar diagram in the workshop on Global Systems but it was not focused on countries in particular. I also find it useful to start with an generic version for systems in general, which I’ll describe later in the tools reference section and then making it specific to a particular system. Here is my first version for countries.

Figure 1: System Environment for a Generic Country.

The diagram shows a country as the focal system, which interacts with its physical environment and with the global economy. It also has a boundary, which has boundary controls. It shows that External Interested Parties have interests in, or concerns related to, the country.

The main value of these types of diagram is that they suggest a set of questions:

- What is that environment and what is the interaction?

- What is the boundary and how is it controlled? It may seem obvious that it is the land boundary claimed by the country, but there is also the question of claims on the surrounding seas, embassies and airports. The controls include both physical border posts and naval patrols but possibly virtual controls on information and monetary flows.

- What are the external interested parties and what are their interests?

The external interested parties include other countries, whose interests may be formal, through treaties, alliances diplomatic or formal colonial relationships, or informal through practises such as resource dependencies and colonial relationships.

They also include institutions which are part of the environment with which countries interact, such as international institutions like the United Nations or global institutions which include global corporations. Note the distinction between “international”, which are nation-to-nation and “global” which relate to their components without using national governments as intermediaries. One drawback of the United Nations is that its governance is through country’s governments, so that repressed minorities in a country have no direct representation. Even nations such as Indigenous nations, which do have some representation do so only at the discretion of their colonisers.

Indigenous peoples are another set of external interested parties; external not because they are not living within the territory claimed by the country―usually that territory was stolen from them―but because many of them are still sovereign in spite of some of their numbers making concessions under duress or sometimes self-interest.

The physical environment is the land, sea and air within the physical boundaries and also those parts of the physical environment outside the boundaries that it interacts with, because they do not respect boundaries. This includes the atmosphere, oceans and transnational rivers, oilfields and aquifers. It may provide resources such as minerals, capacity for agriculture, parks, wild harvests such as fish, and it implies stewardship ― the responsibility to take care of the environment for its own sake, for the use of future generations, and because of the impact outside the boundaries, such as the health of rivers downstream and the quality of the air, neither of which are constrained by country boundaries.

The physical boundary is enforced by physical controls such border guards and military, but also by many virtual controls such as taxation on the flow of capital, constraints on foreign ownership of vital industries and land. Some of this is managed by the government, but some flows are managed by global and international institutions. They are also managed by other countries because in many cases the border is shared with one or more other countries.

Since the diagram is for countries in general, it can still be refined even further to ask specific questions about specific countries. I will do that in later workshops.