Capitalism and Principles

This workshop is intended both as a demonstration of how the rest of the workshops will be structured and to show how principles can be useful as a point of comparison for existing systems, to identify problems.

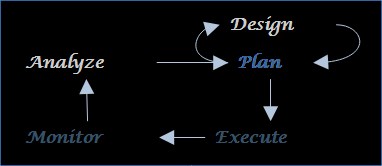

The usual workshop structure has three parts:

- Introduce the tools to be used. In this case, the tool is the use of principles as a foundation.

- Analyze a problem, using the tools. In this workshop, as a means of evaluating capitalism

- Analyze the tools: how did they help and can they be improved?

Let’s begin: what are principles and why do we use them?

First, a definition from a dictionary. The Oxford English Dictionary defines several senses of the word. The three most relevant to the usage in this workbook are:

5 A fundamental truth or proposition on which others depend; a general statement or tenet forming the basis of a system of belief etc.; a primary assumption forming the basis of a chain of reasoning.

6a A general law or rule adopted or professed as a guide to action; a fundamental motive or reason for action.

6b A personal code of right action; rectitude, honourable character

The intent is to make use of all of these, so that we can use principles as a general rule, which is to say something that always applies in the domain that we wish to use it, and from which we can derive more specific rules.

The reason for 6b is that to call someone a person of principles is usually considered to be a compliment. This is because we usually think it implies someone doing what is right in the long run, in spite of the temptation to do what is expedient, perhaps to their own advantage. This may be a good thing, but there are people whose principles can be summed up as “I got mine, screw you!” or even “I believe in the free market and any problems arise because governments interfere too much”.

They are wrong, but if they claim that these are their principles of right action and honourable behaviour, there is little to be done except to show either that they share even more fundamental principles with you and that these conflict with them. Perhaps they would agree that “My own happiness is important to me” and it may be possible to show that selfish people are less happy, or that their lives will be better with a wider government safety net.

Even the “I got mine” crowd should remember that accidents and history happens and that they may lose what they have in both wealth and health and become even more dependent on others than they are.

But if not, this illustrates one main benefit of principles — that we can rely more on people the more we know that their principles are close to our own and that they tend to act in a way that are consistent with their principles.

A second benefit is that we we use principles to agree with other people on how we will behave. By negotiating and agreeing jointly on the principles, through principled discussion and negotiation, we can arrive at a more just society than one in which the rules are arbitrary or imposed by a dictator.

This is why some countries and other organizations have constitutions; a set of principles much more brief than their whole body of laws or regulations, which are the basis of those laws and regulations and which override them if the laws and regulations are shown not to be consistent with them. They typically have a more stringent process for changing them than simple majority votes.

However, principles should not be followed without questioning. If they are shown to lead consistently to bad results, they must be modified. In Canada, the mechanism for changing the Constitution is so difficult, requiring such broad agreement, that a document that was negotiated in a very short time by a particular set of federal and provincial leaders may never be changed again.

The problem to be considered in this workshop is, “is capitalism a good system?”. Is it consistent with a set of ethical principles, either by supporting them directly or at least not being inconsistent? As usual, I try to find a useful starter definition of capitalism by looking at a dictionary to give some sense of the normal usage of the word and then look at the weaknesses of that definition.

As a reminder from the previous workshop, Basic Capitalist bullshit, The Oxford English Dictionary defines capitalism as

An economic and political system in which a country’s trade and industry are controlled by private owners for profit, rather than by the state

In a later project on language, I will take a much deeper look at the limitations of dictionary definitions.

There are possible variations on capitalism, with some suggesting that it’s not capitalism as such that is causing problems, but as capitalism as it is practised in the wealthiest nations. For example, neo-liberals claim that it would be better with less government interference, while most traditional “labour” parties, including Canada’s New Democratic Party, say it needs more regulation. For now, let’s stay with “as it is practised today”. In particular, with large corporations that dominate the economy.

How does it compare with the UN Charter principles? The United Nations Charter starts with a pre-amble, which contains very basic principles:

WE, THE PEOPLES OF THE UNITED NATIONS DETERMINED

to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, which twice in our lifetime has brought untold sorrow to mankind, and

to reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, in the equal rights of men and women and of nations large and small, and

to establish conditions under which justice and respect for the obligations arising from treaties and other sources of international law can be maintained, and

to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom,

With regard to the clause on the equal rights of men and women and of nations large and small, Anatole France’s observation still holds:

The law, in its great concern for equality, forbids rich and poor alike to sleep under bridges, to beg in the streets and to steal bread.

Although it is arguable that capitalism has generated more overall wealth than, for example, feudalism, it has always generated the massive inequalities that leave the poor sleeping under bridges and begging in the streets. It is clear that those who sleep under bridges do not have the same right to shelter and safety as those who live in a mansion in a wealthy area. Many shelters for the homeless are not safe from assault or from the theft of their few personal necessities.

Capitalism does not provide any of the necessities of shelter, food and safety to people who have no money and only provides money to people if they can do profitable work. It has no provisions otherwise. Anybody unable to perform the kind of work that is in demand at the place where they live has no way under capitalism to get food, shelter or health care.

How can working people have the same rights as capitalists when a significant portion of their lives is spent working where they only have the ability to make decisions where it has been delegated to them by their employers. Where those employers are large corporations, they have almost no input.

The granting of wealth and power by accidents of birth isn’t just inherent under capitalism, but seems to be a property of every hierarchical structure, including feudalism. Feudalism is more somewhat more rigid in preventing people from gaining wealth and power through lucky life events but still has many examples of people gaining significant power as advisers to nobility or as merchants.

The principle social structures of capitalism are corporations, which are designed to maximize profit. Some claim that under ideal capitalism, the “invisible hand of the market” will somehow ensure equality but this has never worked in practice.

We have had to invent social structures such as food banks supported by charity to ensure that people don’t starve on the streets, because even attempts to mitigate hunger and homelessness through government action have failed. Certainly, capitalism without other structures operating on other principles fails at this.

It is not even true that the majestic equality of the law is of great help. Black people, people of colour, LTBTQ+, religious minorities, disabled people and many others are actively excluded by employers and landlords, as well as being denied the same access to capital from banks and other lenders. This may be illegal, but the structures of the law do not permit them to claim its help in enforcement. The argument that this bigotry is not a product of capitalism as such, is not valid.

It should be obvious that capitalism is intrinsically unequal from the basic fact that capitalism divides people into at least two classes, those who own the means of production and those who do not but instead are used (that’s what “employed” means) by them to generate profit.

As a starting point for Principles in this workbook, I will use the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. These have had enormous effort spent in developing them and gaining widespread agreement, though some states have been reluctant to adopt them. For example, Canada is reinterpreting them in its own law. It is unlikely I can improve on them, within their scope, especially since principles are of little use unless adopted and used, so nothing I say can be of greater value than something from the UN.

It is very difficult to get agreement on principles on an international scale, so I have no criticism of them. I do have some suggestions for developing principles on a smaller, easier scale. This is largely to reduce ambiguity, which can be a problem internationally, sometimes ambiguity is required to get states to sign; they can then have wiggle-room to apply them in their own context, but it does weaken the ability of the oppressed to hold people to account.

I have adapted the following from the book Design Patterns, by Erich Gamma, Richard Helm, Ralph Johnson and John Vlissides, in which they say that a pattern has four essential elements. Patterns are generic solutions than can be adapted to solve related problems. The technique is very well known and has whole conferences devoted to it. Principles are similar, so I think it is likely that the elements can usefully be adapted.

- The principle name is a handle of a few words we can use to describe it and giving it a handle we can all recognise. .

- The problem describes when to apply the principle. It explains the reason for the principle and the context in which it is applied.

- The solution describes the principle in more detail, how it addresses the problem for which it was created and its relationship to other principles. It doesn’t give a detailed solution for the problem in all its forms, but instead gives a general principle which should be followed by all more specific solutions.

- The consequences are the results and trade-offs of applying the principle. There may be complications and potential abuses.

For example, UDHR Article 23 has four parts:

- Everyone has the right to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favourable conditions of work and to protection against unemployment.

- Everyone, without any discrimination, has the right to equal pay for equal work.

- Everyone who works has the right to just and favourable remuneration ensuring for himself and his family an existence worthy of human dignity, and supplemented, if necessary, by other means of social protection.

- Everyone has the right to form and to join trade unions for the protection of his interests.

We could call the whole article “Justice in employment”. The first part has multiple parts, which could be called “Right to work”.

Right to work could be meant to address two problems. In a capitalist society, untempered by social safety nets, work is essential to provide the income which is the only means by which life can be maintained. It could also mean that work — bodily activity with a meaningful outcome — is important to the physical and mental well-being of most human beings. Was one or both of these the reason for the principle?

Perhaps we can infer that the income is not to be tied to work because article 25 says that

- Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.

- Motherhood and childhood are entitled to special care and assistance. All children, whether born in or out of wedlock, shall enjoy the same social protection.

So it is reasonably clear that it is the meaningful activity that is protected here. In spite of this being a Universal declaration of human rights, it doesn’t seem that even the majority of people have anything resembling free choice of employment or truly fulfilling work. To be honest, I’m puzzled about what was intended by “free choice of employment”. In the UDHR, there is very little solution offered, in the sense of a more detailed description. There is some attempt to group rights into sub-rights as in the numbered points above, but not an attempt to relate the right to employment to that of an adequate standard of living, though if that is intentional, it would be better to say so, possibly under the missing consequences heading.

It is a while since I read the UDHR, I was not surprised by the amount of ambiguity, given the difficulty in getting more authoritarian states to sign it, but I was surprised how far almost all states are from implementing it. You may wish to read it yourself and see if you can complete for the four elements for principles for a few from the little that is given. I found it helpful in understanding what they could mean if it were seriously intended to build a community on the basis of these rights. I will revisit this later.

| Previous: Workshops; Lies, Bullshit and Doublethink | Next: Nation States are a Bad Idea | Return to Table of Contents |