Workbook Introduction

Overall Structure

In this section, I explain the structure of most workshops and a framework for the workbook as a whole.

As mentioned in the introduction, this workbook is a series of workshops. Each one will include some or all of the following.

- An explanation of one or a few tools to be used for the first time, or in an expanded format. In some cases, for more complex systems thinking tools, I will introduce or expand on the tools in a separate section immediately before the first workshop that uses it.

- An introduction to a system which will be analysed in the workshop.

- Discussion of the values — ethical principles, wants and needs — which the system ought to support.

- An analysis of the system using the tools

- Suggestions for improvements to the tools, based on how well they worked in the analysis.

- Suggestions for improvements to the system, or possibly for replacing it.

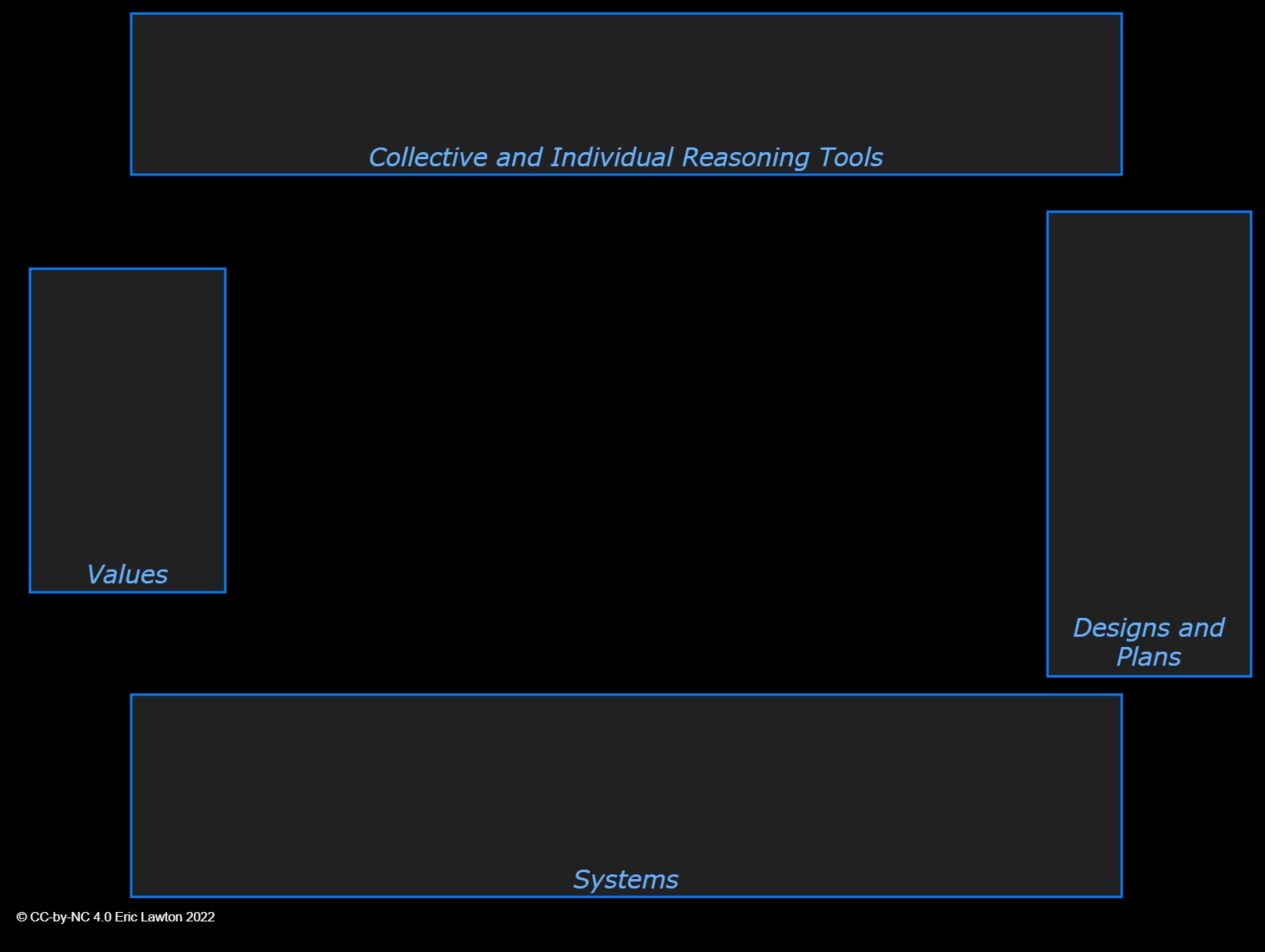

The diagram below summarises this, with four rectangles labelled “Values”, “Collective and Individual Reasoning Tools”, “Designs and plans” and “Systems”.

I will elaborate this diagram in steps, below.

Figure 1: Workbook overview - main topics

I use several types of diagram in this workbook. I find them helpful as thinking tools. Of course, some people are not able to read the diagrams or do not find them useful. Others may need some help for the first few times I use diagrams of a particular kind. However, they are not necessary for understanding the material but are merely a visual summary of the text. I will not provide a separate detailed description of the diagrams, because they add nothing to the text other than as a visual aid.

As also mentioned above, the process for the workshops implies a continuous loop that can go on forever; at least until we have good enough systems and good enough understanding of them. This is unlikely in the next few millennia.

The initial workshop on each system will start by:

- Giving a few reasons to think that the systems have significant adverse effects or do not do what their proponents claim they do.

- Defining the system, first by examining dictionary definitions, then by showing their limitations and how I adapt them for the purposes of this workbook

- Using the initial systems thinking tools to prompt and answer basic question about them.

Later workshop structures will be more specific to each system.

The issues I think are important cannot be addressed merely by changing the thinking of individuals, but will require changing the structure and processes of human systems, as I hope I will demonstrate clearly. Systemic changes will require specific systems and communities to do the changing. That is why many of these tools are taken from work that is described as “systems thinking”, though I prefer the broader term “joined-up thinking” which used to be common in England, but appears less so as populist politicians have abandoned it for a public relations approach to persuasion, including empty slogans and a jovial character as a front-man for the party of the elite. “Synoptic” is another term for it which means both “A summary” (as in “synopsis”) and “taking or involving a comprehensive mental view”, so I sometimes use that too.

In order to tackle complex issues, we have to circle around the issues many times, for several reasons.

The first, inner loop is that we have to learn as we go. The projects will start with simplified versions of both tools and systems. As Daniel Dennett says in his book “From Bacteria to Bach and Back: The Evolution of Minds”:

Our path will have to circle back several times, returning to postponed questions that couldn’t be answered until we had a background that couldn’t be provided until we had the tools.

Since the task is cyclical, we have to begin somewhere in the middle and go around several times.

I will start with Values because in order to analyse the current systems, it is useful to have some idea of what we would ideally want our systems to do, so that we can see how, according to our monitoring, they do what we would like them to do.

This will not be the same in detail for everyone; uniform systems and cultures are not only not possible, they are not desirable.

However, we are often told why systems such as capitalism and liberal democracy are valuable, so we can start by seeing if they conform to their own ideals and to those which have been arrived at after much debate, such as the United Nations declarations on Human Rights and the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and various rights embedded in the constitutions of eurocentric countries. Even a cursory look suggests a large gap between such principles an the actual behaviour of the current colonialist systems that seek to assimilate Indigenous and minority cultures.

The second loop comes from the nature of the systems. As we will see, the most important systems have feedback loops inside them, which is what allows them to survive in a changing environment. In order to understand them, we need to know follow the flows of resources and information around those loops several times before we can begin to understand them.

The third loop is that when we have become more skilled in the use of the tools, we will find that they don’t work as well as they could and we will have to improve their design or replace them. Then we will have to reapply them to see how it changes our understanding.

I described the fourth, outer, loop above. It results from the changes in systems, both those consciously designed and planned and those which arise from the dynamic nature of systems and history.

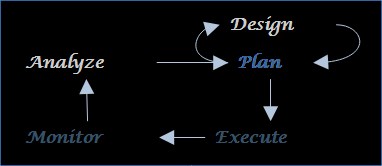

One way to look at it is to use the concept of a MADPE loop, which stands for:

Monitor — the current systems

Analyse — the results

Design — an improvement

Plan — for change

Execute — the plan

Then continue by monitoring the results of the changed system and so the loop continues.

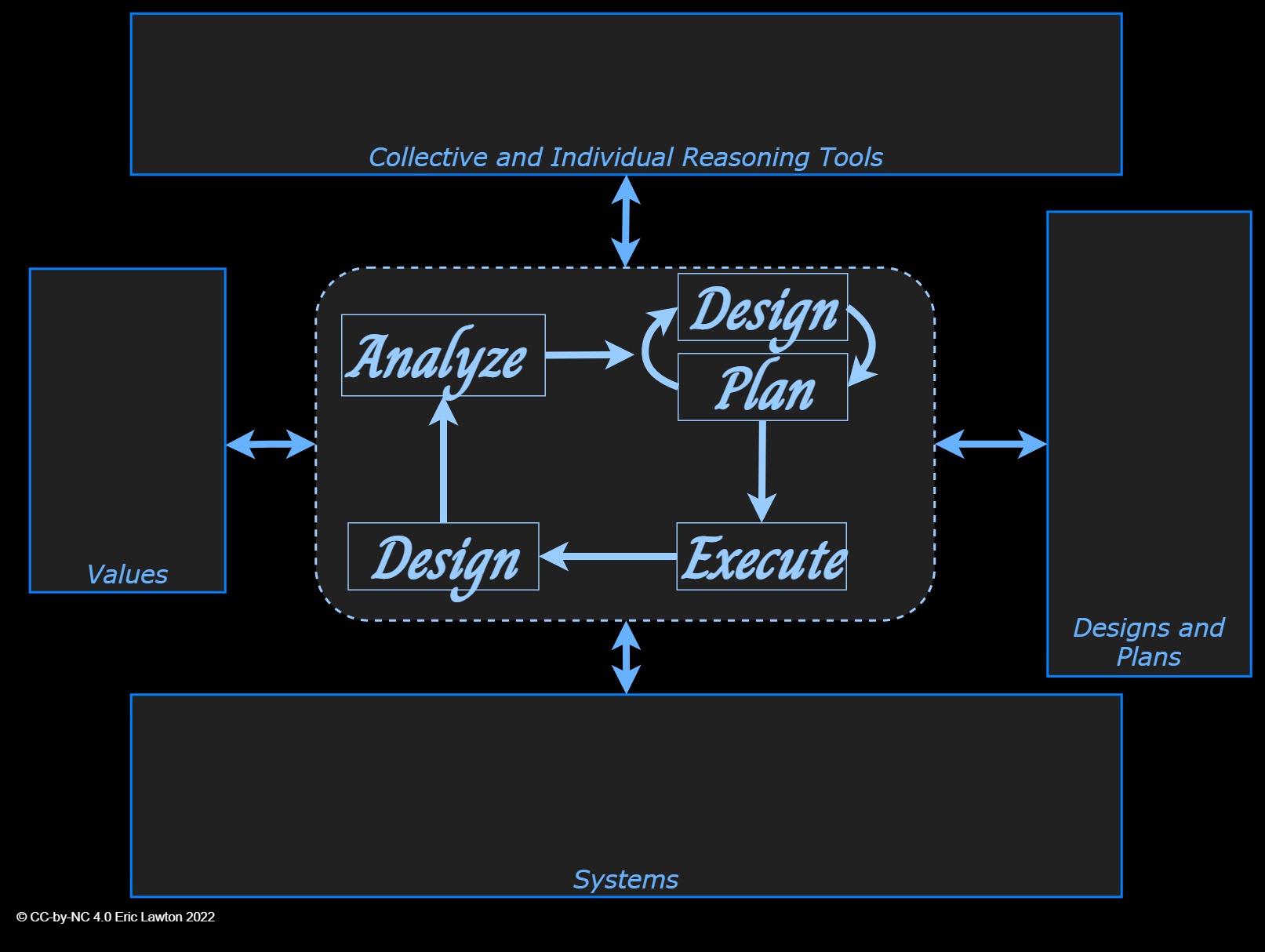

This loop is shown at the centre the diagram below and provides a useful summary of the whole approach.

The focus of this workbook is on the Analyse and Design and Plan steps, though I will comment on the other steps on occasion. It will also omit many other approaches, on the weak but necessary grounds that I do not have expertise worth sharing, especially non-eurocentric approaches, but including many parts of eurocentric knowledge in the humanities, arts, science, engineering and technology that are relevant but beyond my expertise.

I will only look at eurocentric systems. Other nations and cultures have other systems, many of which are not prone to the problems caused by the explosive growth driven by capitalism and colonialism. I do not know enough about these to analyse them in any useful manner, or even whether the tools I use are particularly applicable, though I am attempting to learn.

The first passes around the MADPE loop will look at existing systems. Suggested improvements will be in the context of today’s systems.

Since many of the systems monitor themselves, producing huge volumes of statistics and reports and, in the case of the media and other institutions, monitor other systems, we can use existing results as the initial Monitor step of our loop and begin with the analysis. The analysis begins with understanding how the systems work and how their actual performance — as opposed to their claimed effects — implement desirable values or has undesirable effects. This gives a logical entry point to start the loop.

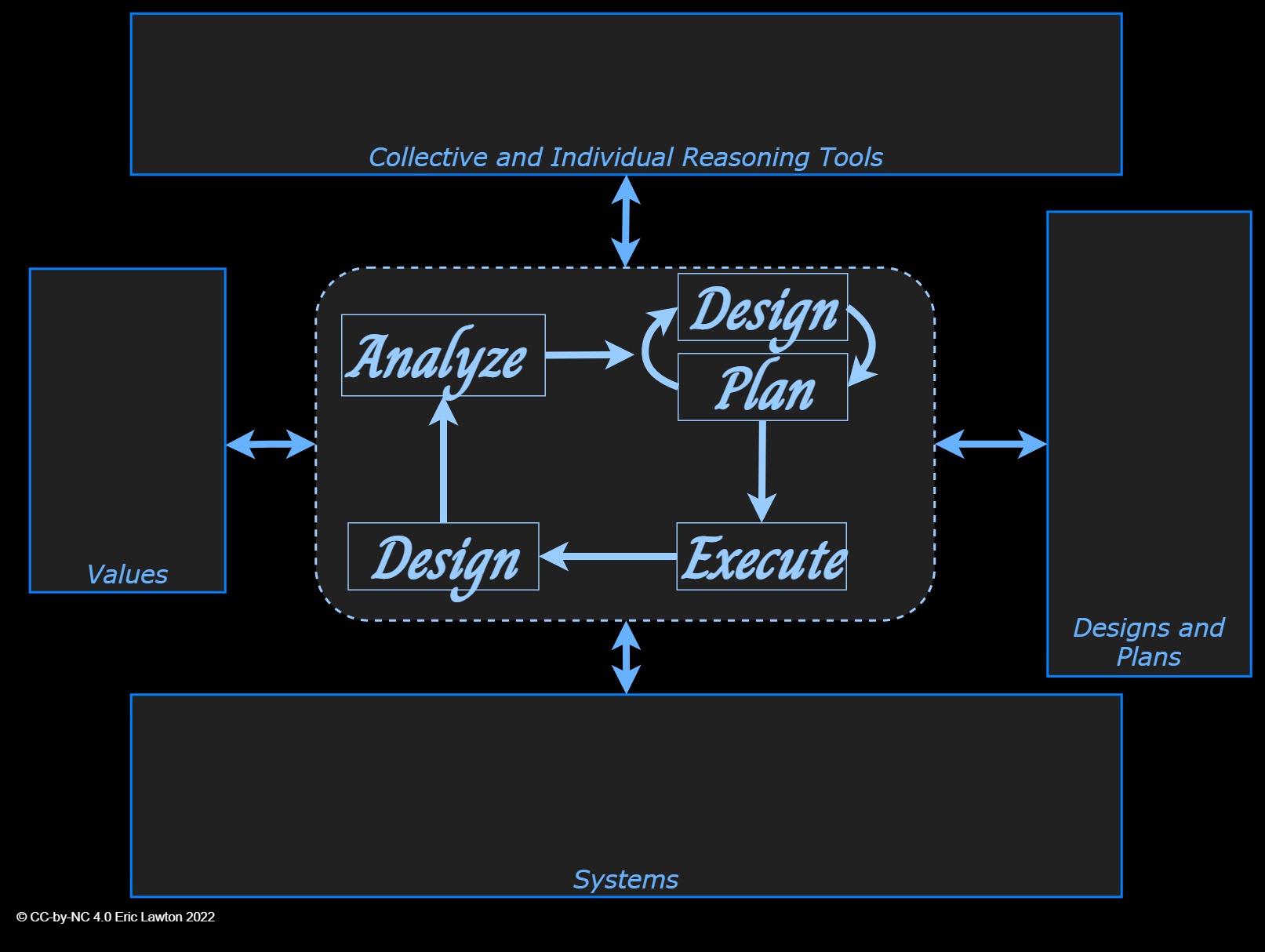

Figure 2: Workbook overview - MADPE loop

The workbook is structured around the loop described above, with a central loop going from Analyze to a smaller loop of Design and Plan a future, based on the results of the analysis, then to Execute the plans and then Monitor the results, from which we return to the Analyse phase to make sure the consequences are what we intended and to look at next steps.

The two-way arrows connecting the MADPE loop to the four rectangles represent the inner loops in which the values, tools, designs and systems representations are four rectangles positioned around that central loop, which represent our current requirements (what we would like to see in the future), the tools we will use to do the work, the resulting designs and plans and the current and future systems which are the objects we work on through this process.

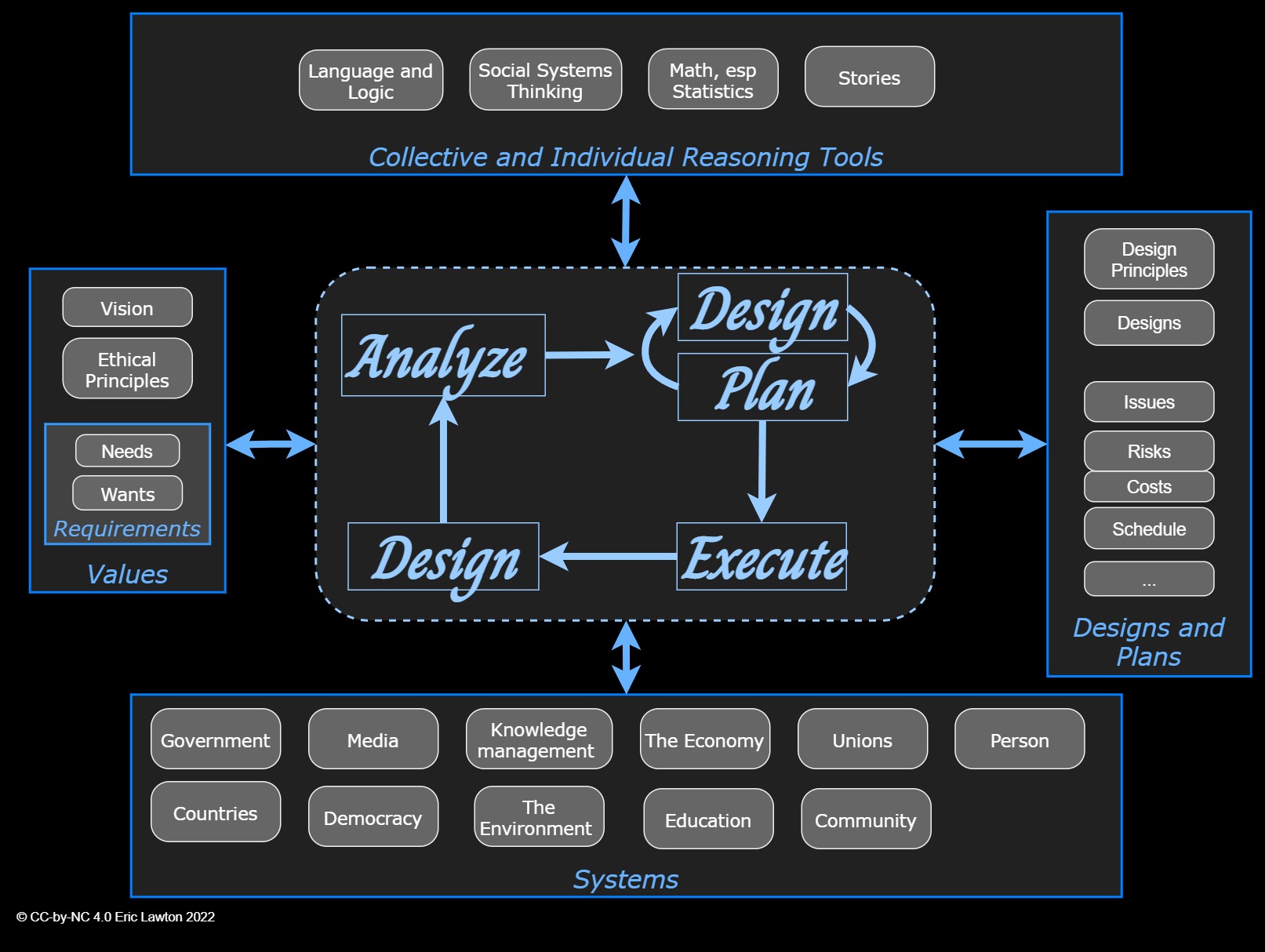

Each of these four rectangles contain further elements.

There are many which could have been included, such as the tools for organising communities, but although I have some experience, I do not consider myself expert enough to offer comment more useful than others are providing.

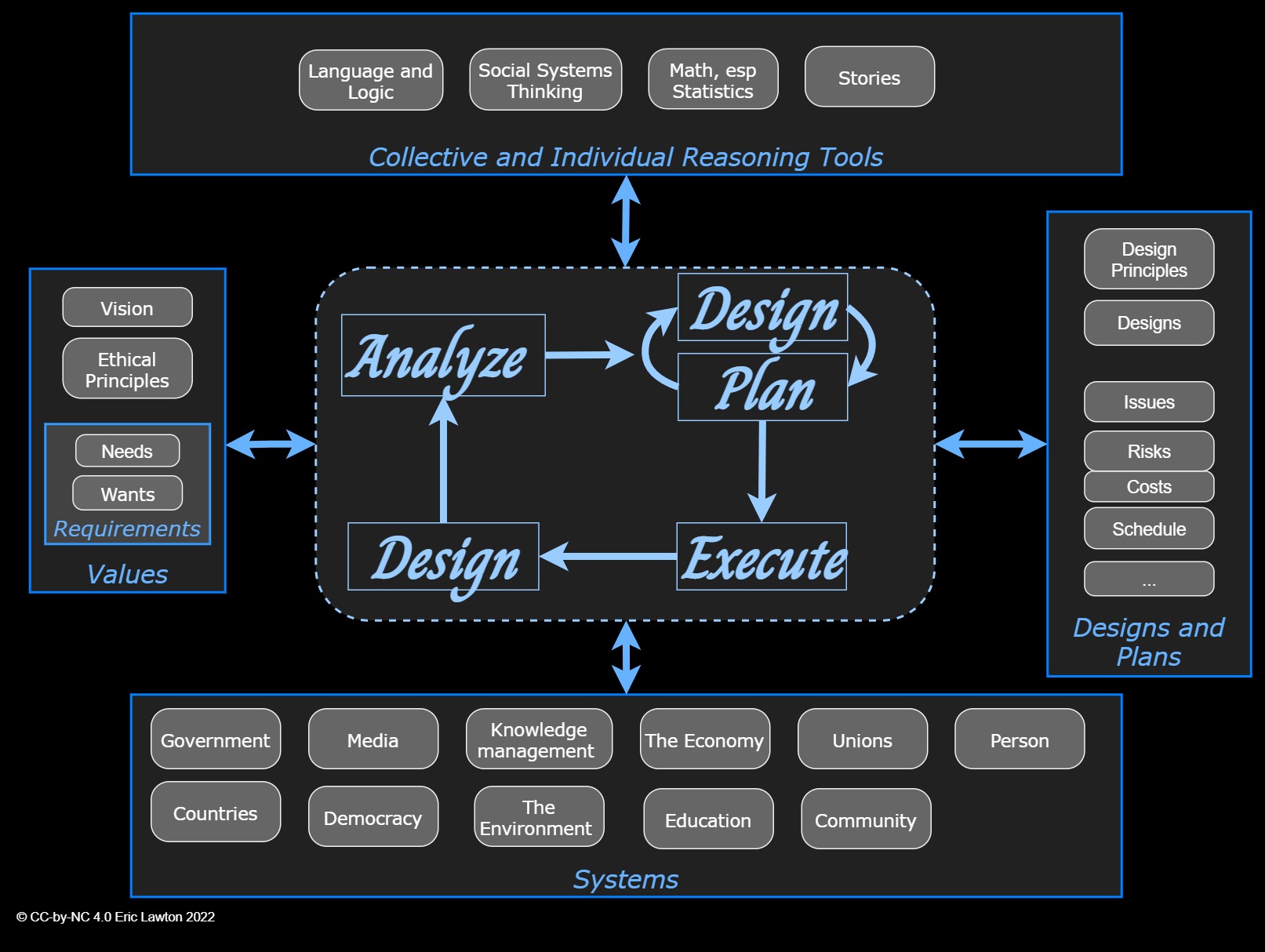

Figure 3: Workbook details

The values represent the intentions behind the system. They may include things like a Vision for the system, the guiding Ethical Principles and Requirements, which in turn consist of Wants and Needs, which will be explained further as we go. Many of these should be defined at the community level and I cannot speak for most of them but will discuss both my own and some with global history such as the United Nations Declarations of Human Rights and Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The Collective and Individual Reasoning Tools box contains Language and Logic, Social Systems Thinking, Mathematics especially statistics and Stories. I specified “Collective and Individual” reasoning for reasons I will detail later but to draw attention to the fact that our reasoning is not just an activity we can perform by ourselves, but a process by which communities arrive at knowledge and decisions.

Designs are often created by using a set of design principles which have been proven through previous failures and successes.

Planning results in a set of plans, which include not only of a schedule (actions and times) but also of issues, risks, costs, feasibility assessments and more. These will be described later.

The reason for the iteration between design and planning is that without a plan to implement a design, it is useless. It may be that it costs too much for the benefit it delivers or for the available resources, or it may be too risky, or any of many reasons which planning an implementation might reveal. However, the problems revealed may suggest a change in design which may provide the benefits hoped for, while being easier or safer to implement.

Finally, the loop concerns itself with specific systems, both current and future, which include Government, Media, Knowledge Management, the Economy, Unions, Persons, Countries, Democracy, The Environment, Education, Community and many more, though those mentioned here will be the focus of the workbook.

Because of this, my initial workshops on each system start with a few major reasons to think they are not working in our best interests. Then I make a first attempt at a definition of the system, starting with a dictionary definition from the Oxford English Dictionary, with a look at Merriam-Webster if it differs significantly. Then I ask if there are problems with the usefulness of the definition, including clarity. If necessary, I introduce my own definitions, as close as possible to the dictionaries’ definitions.

Next, I apply a framework for understanding social systems which I will outline in the next section, before starting the workshops. The framework isn’t intended to capture everything about every system, but rather to capture some questions that are usually worth asking.

My white, cis, heterosexual, male, opinions on what the world should look like are of no great interest or value. They are included only for the sake of illustrating the method and tools.

Principles, including human rights, do not come from the sky but are worked out carefully so that in the end the systems that follow the principles seem to be the best we can do at the time; another consequence of the circles described above.

The principles here are ethical principles: guidelines on how we should behave and how systems should behave. There are other kinds of principles which are closer akin to design tools, such as the principle that systems should not have a single point of failure.

But eventually, times change; unforeseen problems become visible and the principles need changing. And people will still find ways of abusing and distorting them, such as the use of the principle of “free speech” being used by fascists demanding a platform. They need careful wording and delimitation when they are specified.

The tools in the box across the top are a few examples of some I have found useful. They all include elements of bullshit detection which became less necessary with leaders like Donald Trump or Boris Johnson, where the nonsense is so blatant that it hardly needs detection unless you are so bewitched by your fandom that you will believe that your leader is holding up 15 fingers if they insists that they are.

I have adapted the language and logic tools from my studies of academic philosophy; they can be the basis of communication and collaboration but can only address simple concerns. More complex tools are required to understand systemic issues because complex effects can follow from simple changes.

To gain even more understanding, more advanced techniques, such as mathematics or social sciences are required but I won’t go into any details of those here, just some indications of how and when they are useful with some basic ideas from statistics.

To complete the cycle, in the rectangle on the right are elements of plans for making changes. Again there is a specialized discipline, project management, that provides a lot of tools for creating and representing such plans. I won’t do anything more here than sketch them to the level where it becomes obvious why this is more complex than most people seem to think, or that many politicians want you to think so that you do not realize how little competence they have, in skills that are required for their job. However, there is a reason why several of the technical professions which are involved in larger projects, such as engineering, architecture and IT architecture require their practitioners to have a working knowledge of project management.

This should include political decision makers. It is ridiculous that we elect people to those jobs with no relevant skills, let alone a portfolio of work showing their projects and the end result.

After the workshops you will find the finished products. “Finished” means at the end of the work in this workbook, which I hope will be useful to feed into other work. As the tools were refined and extended in each workshop, I will update a stand-alone section on each of the tools, which summarizes the lessons from the individual workshops. It follows a standard pattern of describing the tool, how to use it and how to assess when it is useful, when it is not. This can be used as a reference.

This MADPE loop will guide the structure of the whole workbook. There is another, inner loop which I will use as a model for the structure of the individual workshops. That loop is used to refine our understanding of a particular situation, whether that is past, current or imagined future.

I use an initial set of thinking tools to analyse the state of the current systems and possibly to plan some changes, then analyse the process I just went through, looking for difficulties that suggest that the thinking tools themselves need refining or replacing. I will call this inner loop Analyse, Plan, Critique (APC).

I took the original MAPE loop idea from the design of autonomic systems: computer systems that could adjust themselves to meet a limited change in circumstances according to pre-programmed rules, shifting resources from one task to another, but unable to change their design or to critique those rules. Fortunately, the engineers designing such systems already used a different word — autonomic — to refer to that limited capability, so the use of the word adaptive can be reserved to mean those more flexible systems which can adapt more radically to change, including the ability to change their own design.

Previous: Rationale: What’s in it for us? | Next: Workshops: Structure of the Workshops | Return to Table of Contents